When I see an adult on a bicycle, I do not despair for the future of the human race. - H.G. Wells

Welcome

History 499: Social History of the Bicycle

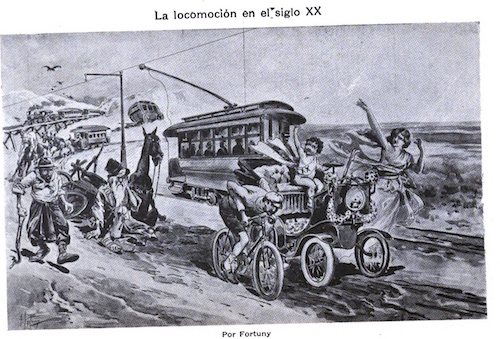

Over the last twenty years, the bicycle as a form of transit and leisure has seen a huge resurgence. Global cities from Copenhagen to Paris, New York to Washington, Mexico City to Buenos Aires have increasingly encouraged cycling as an aid in reducing the social, health, and environmental problems caused by automobile pollution, congestion, and infrastructure. Interestingly, utopianist advocates of the bicycle as a revolutionary means of promoting individual and environmentally-friendly mobility are looking to the one of the most persistent of nineteenth-century technologies. In the 1880s and 1890s, bicycles did revolutionize the social, gender, and physical infrastructure of the cities where it was adopted. The cyclical return of the bicycle has a history. This course will follow the social history of the bicycle by investigating its technological, gendered, and cultural impact in cities around the world. Bicycles carry a particular ambivalence socially and historically– they are transportation and sport, work and leisure, technology and icon, tool and toy. This ambiguity opens a huge array of potential topics that can be analyzed via the bicycle. Students will write research papers on some aspect of the bicycle’s social impact, in the United States or abroad.

contact

where to find me?

contact

Prof. Chad Black

Email: cblack6-at-utk.edu

Phone: 974-9871

Office: 2627 Dunford Hall, 6th Floor

Office Hours: Tuesday, 3:00-4:00, Wednesday, 3:00-4:00

Course Objectives

what are our goals?

course objectives

Department guidelines for 499 set the following expectations for students:

-

to research and write a paper that displays the skills they have learned throughout the major;

-

to learn to develop a research question;

-

to learn to build an argument using primary sources and relevant secondary literature;

-

to do history on another level, not merely as consumers but as writers of history;

-

to progress to a stage where they can conduct research and teach themselves things they don’t know;

-

to learn to take a large volume of information and explain it in an intelligible format.

These skills will culminate in the student writing a 4,500-6,000 word research paper in which they advance their own historical argument. We will work on these goals on paper and in discussion.

Reading, writing, and oral assignments for this course are designed to meet these goals. In meeting them, you will also be able to place the bicycle in its historical contexts and ambiguities– as sport, technology, leisure, work, transport, etc.

readings

what are we reading?

required readings

The following books are required for this course. They can be purchased at the bookstore, or likely for cheaper on the interwebs.

-

Guroff, Margaret. The Mechanical Horse: How the Bicycle Reshaped American Life. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016.

-

Ritchie, Andrew. Major Taylor: The Extraordinary Career of a Champion Bicycle Racer. Balitmore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

-

Smethhurst, Paul. The Bicycle: Towards a Global History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Additional readings will be available in a dropbox folder I will share with enrolled students, or via the university library’s website.

requirements

what are we doing?

course requirements

assignments

The assignments in this course are aimed at helping, step by step, the student to successfully accomplish a semester-long research project. We will be reading widely, across topics that intersect with the bicycle. We will also be writing regularly, sharing our writing with each other, and spending a lot of time in discussion.

-

Memo writing (20%). As part of developing your research skills, each student is required to write a memo using this form for assigned readings. Memo writing hones your ability to summarize and synthesize. Some readings will deserve longer memos than others. This technique will be important for your literature review, and your paper as well.

-

Short literature review, 3-4pp (10%). Students will write a short paper that analyzes two or three scholarly works (monographs or peer-reviewed articles) from appropriate academic resources. This paper should demonstrate a working knowledge of the major debates in the larger field you will be writing on (sport, technology, gender, race, urban histories, etc.). What are the main questions that scholars are asking about your topic? How are they answering those questions? What are their arguments and how do they interact with those offered by other historians? If you write good memos on what you have read, this will be a very straightforward assignment.

-

Short primary source analysis, 2-3pp (10%). Students will write a short paper that establishes the context and significance of one or two primary sources that are important to your final project. This primary source analysis should be suggestive of the future direction of your paper. Why is the source important to understanding a core issue in the past?

-

Annotated bibliography (10%). Students will construct a bibliography of the secondary and primary sources for their project.

-

One sentence, one paragraph, one page (10%). In this exercise, students will explain their projects in those chunk-sized bits of text.

-

Final paper (40%). The paper to end all papers. Students will write a research paper of 4,500-6,000 words in length. The paper will have a bibliography. The topic will be of the student’s choosing, and will use the bicycle as a foil to analyze broader social or cultural issues, such as gender, race, sport, class, invention, urbanity, work, youth, etc. At the professor’s discretion, students may also choose a different everyday technology to analyze the way we have the bicycle.

policies

things to know

policies

Qualified

students with disabilities needing appropriate academic adjustments should

contact me as soon as possible to ensure that your needs are met in a timely

manner with appropriate documentation.

Qualified

students with disabilities needing appropriate academic adjustments should

contact me as soon as possible to ensure that your needs are met in a timely

manner with appropriate documentation.

Attendance: Attendance at all class sessions is mandatory. We only meet once a week. If you miss one class, you’ve missed an entire week of class. Discussion, group editing work, etc. that is done in class is indispensable to successfully finishing your paper. If you will not be able to attend class, please contact me ahead of time.

Deadlines: Assignments must be emailed to the instructor no later than the beginning of class on the day they are due, or at some other specified time established by the professor. It is important to be technologically savvy in today’s world. Much of our communication occurs through email, including the sharing of documents and other work product. Late papers will not be accepted for any reason without prior arrangement. This includes technology problems. You’re responsible for attaching your work correctly and sending it in on time.

Cell Phones and Laptops: Please silence our cell phones prior to class. Please do not text during class. Laptops are allowed only for tasks that require them, as specified by the professor. In other words, plan to have paper with you. We’ll only be using laptops for specific exercises. Based on the prevailing literature, hand note-taking– both while reading and in class– leads to substantially better educational outcomes. You are not required to have a laptop in class, so feel free to leave it at home.

Office Hours: Students are strongly encouraged to speak with me outside of class. The advantages of talking with me include: extra help on an assignment or preparation for an exam; clarification of materials covered in lecture, discussion of my comments on your work; discussion of this or related courses. I am available during office hours on a first-come, first-served basis; if you cannot come by during office hours, please contact me via email or phone and I will be happy to set up an appointment with you.

Changes: I reserve the write to change this syllabus as the semester progresses. This is not a contract, but rather a document to guide expectations and clearly communicate weekly assignments. Please bring the syllabus with you to our class meetings. Or, keep up with it on the course website.

schedule

when are doing stuff?

schedule

Reminder: pdfs are available in the Dropbox folder I provided over email.

We will divide each class meeting into three parts– lecture, discussion, and laboratory. Quotes in the schedule were drawn from Michael Carabetta, Words to Ride By: Thoughts on Bicycling (San Francisco: Chronicle Press, 2017).

Week One – Introduction (August 23)

The very existence of the bicycle is an offense to reason and wisdom.

P.J. O’Rourke

Read:

- Syllabus!

Lab:

- Bicycle Thieves (1948), as you watch the film, make note of every thing you think the bicycles in the film symbolize.

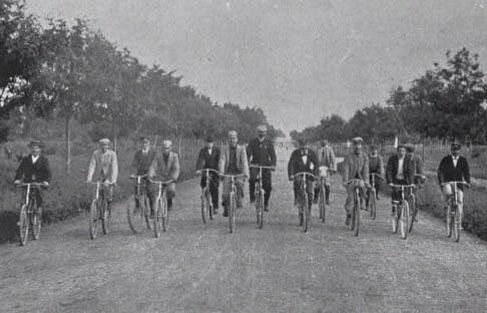

Week Two – The Global Bicycle (August 30)

Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance you must keep moving.

Albert Einstein

Read:

- Paul Smethurst, The Bicycle: Towards a Global History, whole thing. (It’s only 150 pages!)

Write:

- Smethurst Memo.

Lab:

- Library scavenge.

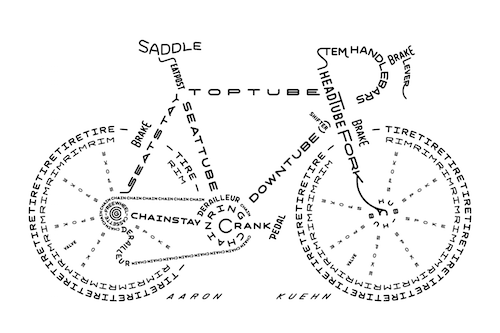

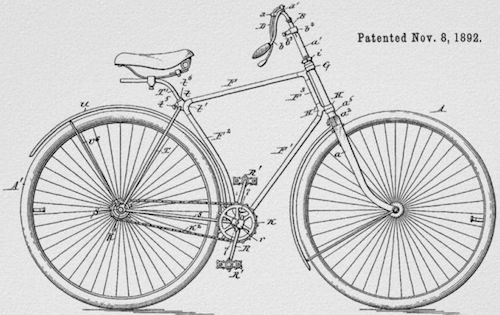

Week Three – Bicycle as Artefact (September 6)

So perfect is the safety bicycle, in fact, that, if the rider had sufficient skill not to interfere with its action, it will travel straight ahead and keep its own balance.

E.J. Prindle, Scientific American, 1896

Read:

- Margaret Guroff, The Mechancial Horse, Introduction and Chapter 1.

- Wiebe E. Bijker and Trevor J. Pinch, “The Social Construction fo Facts and Artefacts: Or How the Sociology of Science and the Sociology of Technology Might Benefit Each Other,” Social Studies of Science, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Aug, 1984), 399-441.

- Nick Clayton, “SCOT: Does It Answer?”, Technology and Culture, Vol. 43, No. 2 (Apr., 2002), 351-360.

Write:

- Memos for Bijker & Pinch and for Clayton.

Lab:

- The Velocipede Craze through the eyes of Scientific American. Skim the articles before class. Most of them are less than a page. We will be working in groups on the document set for the lab portion of class.

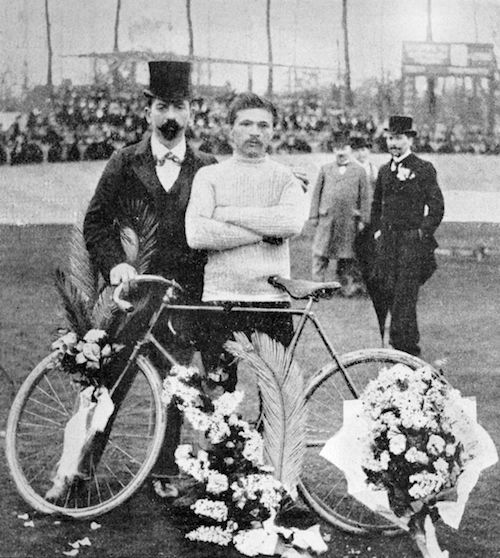

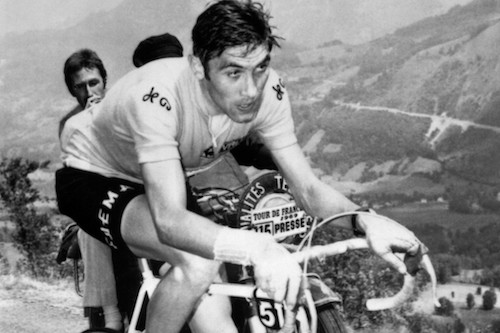

Week Four – Bicycle as Sport (September 13)

Of all sports, cycling is the one that requires the most perfect match of man and machine. The more perfect the match, the more perfect the result.

Paul Cornish

Read:

- Allen Guttmann, “Play, Games, Contests, Sports” and “From Ritual to Record,” in From Ritual to Record: The Nature of Modern Sports (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

- Guroff, Mechanical Horse, Chapter 2.

- Christopher Thompson, “What Price Heroism? Work, Sport, and Drugs in Postwar France,” Tour de France: A Cultural History (Berkely: University of California Press, 2006).

Write:

- Memos for Guttman and Thompson.

Lab:

- Sign up for next weeks individual meetings.

- August 5th, 1897. Bearings Magazine. Look at the race reports, the ads, the photos. What do they tell us about early cycling as a sport?

Week Five – No class. Individual Meetings with Dr. Black. Make (September 20)

If the constellations had been named in the twentieth century, I suppose we would see bicycles.

Carl Sagan

Due: Preliminary Topic and Annotated Bibliography to Discuss.

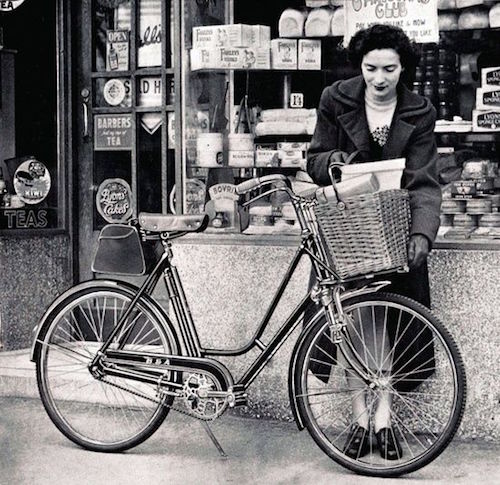

Week Six – Bicycle as Work (September 27)

Get a bicycle. You will not regret it, if you live.

Mark Twain

Read:

- Guroff, Mechanical Horse, Chapter 10.

- David Herlihy, “Utilitarian Cycling,” in Bicycle: The History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004).

- Evan Friss, “Riding for Utility: The Commuters” in The Cycling City: Bicycles and Urban America in the 1890s (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

Write:

- Memos for Herlihy and Friss.

Lab:

Week Seven – The Bicycle and Space (October 4)

Most bicycles in NYC obey instinct far more than they obey the traffic laws, which is to say that they run red lights, go the wrong way on one-way streets, violate cross-walks, and terrify innocents, because it just seems easier that way. Cycling in the city, and particularly in midtown, is anarchy without malice.

The New Yorker, “Talk of the Town,” June 9, 1986

Read:

- Guroff, Mechanical Horse, Chapters Four and Five.

- Evan Friss, “Rules of the Road” and “Good Roads.”

- Robert L. McCullough, “Country Riding,” Old Wheelways: Races of Bicycle History on the Land (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2015).

Lab:

- Browse one of the two League of American books in our pdf folder. One was published by the Ohio Division in 1891, and includes maps and articles about good roads in that region. The other lays out cycling facilities in a 50 mile radius around NYC.

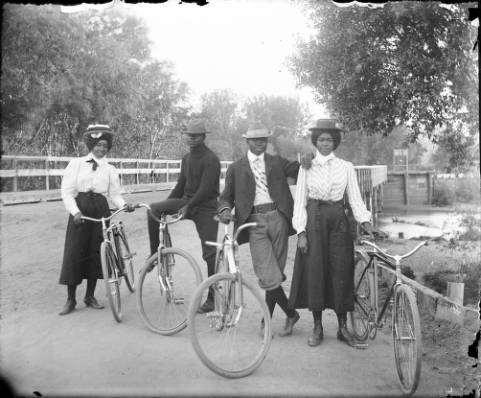

Week Eight – The Bicycle and Race (October 11)

Read:

- Give Major Taylor a full go.

Write:

- Ritchie memo.

Lab:

Research Groups.

Week Nine – The Bicycle and Gender (October 18)

Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives womena feeling of freedom and self-reliance. I stand and rejoice evert time I see a woman ride by one a wheel… the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood.

Susan B. Anthony

Read:

- Freewheeling

- Guroff, Mechanical Horse, Chapter 3.

- Patricia Vertinsky, “Exercise, Physical Capability, and the Eternally Wounded Woman in Late Nineteenth Century North America,” Journal of Sport History 14.1 (Spring 1987), pp 7-27.

- Shelley Lucas, “Women’s Cycle Racing: Enduring Meanings” Journal of Sport History 39.2 (Summer 2012): 227-242.

Write:

- Memos on Vertinsky and Lucas.

Lab:

- Secondary Literature Review Due.

Week Ten – The Bicycle and Empire (October 25)

It’s not about the bike.

Lance Armstrong

Read:

- Guroff, Mechanical Horse, Chapter 7.

- William Beezley, “The Porfirian Persuasion,” in Judas and the Jockey Club.

- Edward J.M. Rhoads, “Cycles of Cathay: A History of the Bicycle in China” Transfers 2.2 (Summer 2012): 95-120.

- David Arnold and Erich DeWald, “Cycles of Empowerment? The Bicycle and Everyday Technology in Colonial India and Vietnam,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 53.4 (2011): 971-996.

Lab:

- Primary Source Analysis Due.

Week Eleven – The Bicycle and Youth (November 1)

As a kid I had a dream– I wanted to own my own bicycle. When I got the bike, I must have been the happiest boy in Liverpool, maybe the world. I lived for that bike. Most kids left their bike in the backyard at night. Not me. I insisted on taking mine indoors and the first night I even kept it in my bed.

John Lennon

Read:

- John Bloom, “‘To Die for a Lousy Bike’: Bicycles, Race, and the Regulation of Public Space on the Streets of Washington, DC 1963-2009,” American Quarterly 69.1 (2017), 47-70.

Write:

Precis for Bloom.

Watch:

Lab:

- In class, watching Breaking Away (1979).

- The Don’ts of Bicycling (1969)

- Ideas for the Bicycle Institute

Week Twelve – Writing Groups, Editing, and Meetings with Dr. Black (November 8)

The bicycle is a curious vehicle. Its passenger is its engine.

John Howard

- One Sentence/One Paragraph/One Page Due.

Week Thirteen – The Bicycle’s Future Past (November 15)

Think of bicycles as rideable art that can just about save the world.

Grant Petersen

Read:

- Zack Furness, One Less Car: Bicycling and the Politics of Atumobility

- Melody Hoffmann, Bike Lanes are White Lates

- E.C. Claxton, “The Future of the Bicycle in Modern Society,” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 116.5138 (January 1968), pp 114-134.

Write:

- Memos for Furness, Hoffmann, Claxton

Lab:

- Research Groups.

Week Fourteen – No class. Writing time. (November 22)

Week Fifteen – Presentations (November 29)

Final Paper Due: Wednesday, December 13th 7:15pm